To mark International Women’s Day on March 6, 2017, DataGueule broadcast a program on France 4, Youtube and DailyMotion, to raise awareness about gender inequality. Entitled “Liberté, égalité, adelphité”, it created huge buzz that spread throughout social networks within a few short hours. But what is this idea of “adelphity” that may drive out “fraternity” from the French republican motto?

(Allons) Enfants de la matrice![1]

Adelphite comes from the Greek word δελφύς which means “matrix”, or “uterus”. Used as a suffix, -delph has given rise to a number of scientific terms relating to the female genital organs: for example, didelph is used to describe certain animal species which nurture their unborn young in two pockets, such as kangaroos or koalas.

Adelphite comes from the Greek word δελφύς which means “matrix”, or “uterus”. Used as a suffix, -delph has given rise to a number of scientific terms relating to the female genital organs: for example, didelph is used to describe certain animal species which nurture their unborn young in two pockets, such as kangaroos or koalas.

Ulysse et ses “frères” d’équipage

The suffix – delph has also given rise to the word “adelph”. During Homer’s time, it was used instead of “phrater” to mean “brother”. According to John V. Fine, a historian at the University of Michigan and author of a critical history of ancient Greek, it must be understood as a desire to understand fraternity not as a literal notion but as belonging to a matrix community. As such, from its beginnings, “adelph” lauds the fraternal bond, the root of a shared origin and the adherence to a sort of “togetherness”.

From brothers in religion to brothers in the Republic: sharing a destiny

Sacred texts used the term “brothers” to describe followers and disciples of a prophet, then, by extension, members of the religious community. United by values, in solidarity with each other, helping each other and sharing the pain of attacks suffered by one of their own or those that targeted all or part of the community.

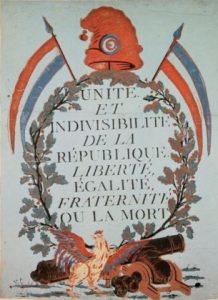

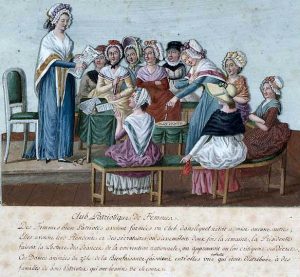

Estampe du XVIIIè siècle

The modern Republic, as it emerged in France after the Revolution, saw fraternity as a unifying sentiment, one that would bring to life a spirit of togetherness in the united nation. All brothers, whoever they may be, wherever they are from, whatever other affiliation they claim or allegiance they make, also submit to the ultimate allegiance: the recognition of the Republic.

Although it has its roots in politics, fraternity was incorporated into the French constitution of 1848 as a social mission: the Republic must “provide for needy citizens, either by offering them work within the limits of its resources, or by providing, in place of their family, assistance to those who are unable to work” by demonstrating fraternal assistance.

Recognition in “universal” fraternity.

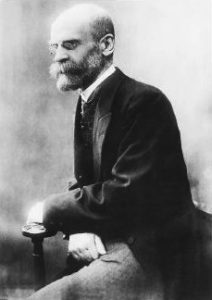

Emile Durkheim

Fraternity became almost synonymous with national solidarity, according to the doctrine of the “father of sociology” Emile Durkheim, who established the concept of a “collective consciousness”. This collective consciousness is what results when common values are shared within a group or society and, as a primary factor in the social bond, a collective consciousness is achieved by recognizing similarities: each individual first sees his or her own kind in the other person. This primary equivalence between individuals imposes an obligation which is set apart from free will: it is the duty of all citizens, regardless of individual preferences and personal choices, to support one person or another according to specific affinities. This so-called “mechanical” solidarity is the foundation of the major human rights principles and duties: the prohibition of servitude, the right to asylum, and the duty to assist the vulnerable or those who are in danger.

La Déclaration Universelle des Droits de l’Homme de 1948

Created and developed in France during the nineteenth century, this vision of fraternity is echoed in the fundamental ideas about universality that have been formalized and endorsed by the UN. From its preamble, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights mentions the “human family” and in its very first article enshrines “the spirit of fraternity”. Humans are born “free and equal in dignity and rights” and “must act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood”.

A fraternity that excludes sisters?

Les clubs féminins de la Révolution française posent d’emblée la question de la place des “soeurs” dans la “fraternité”

So does this only apply to brothers? What about sisters? The question has been on the table since the French Revolution. The women’s clubs of 1789 (which were banned after 1793) made it clear that equality-based citizenship had been established between men/brothers, and women were deprived of political and economic rights… even though brothers would be nothing or nobody without the same mother (whether real or symbolic). The “fathers” of the Revolution decided that feminine referred to the mere function of matrix and nurse, and the Republic recognizes women only through this symbol (of which Marianne is one of the most obvious incarnations).

For Réjane Sénac, an expert political scientist on gender equality, there exists an “original sin” committed by the French Republic, and by extension all those who take it as a model, that fails to dispel the expectation for women to project themselves into a universe which is conceived and written in the masculine. Indeed,  women, who were dismissed from citizenship when it was first established, had to fight to gain the fundamental rights that men had granted themselves unconditionally. The history of women’s rights, which are first and foremost, human rights, which women (as members of the human race until proven otherwise) should legitimately enjoy, is a story peppered with fighting… and debates. Réjane Sénac underlines that for a long time, women’s essential “diminishment” (that is, proceeding from their very “nature”) was highlighted in order to restrict their participation in citizenship, society and the economy: they are less-than-brothers. Then things began to change and women were expected to demonstrate their “added value”: they were said to be better-than-brothers, especially reputed to be more equipped with “soft skills”, that would “complement” the traditional skills that would be essential to current and future performance.

women, who were dismissed from citizenship when it was first established, had to fight to gain the fundamental rights that men had granted themselves unconditionally. The history of women’s rights, which are first and foremost, human rights, which women (as members of the human race until proven otherwise) should legitimately enjoy, is a story peppered with fighting… and debates. Réjane Sénac underlines that for a long time, women’s essential “diminishment” (that is, proceeding from their very “nature”) was highlighted in order to restrict their participation in citizenship, society and the economy: they are less-than-brothers. Then things began to change and women were expected to demonstrate their “added value”: they were said to be better-than-brothers, especially reputed to be more equipped with “soft skills”, that would “complement” the traditional skills that would be essential to current and future performance.

Liberty, equality, adelphity… For truly universal “human” rights and a social organization that is more egalitarian than “binary” and “complementary”

Penser la diversité par rapport à une norme centrale à partir de laquelle se définissent des “différent.es” fait obstacle à l’égalité réelle

Given these conditions, is it truly possible to achieve genuine equality? Because in this configuration, “brothers” still occupy the leading and central positions in the order of legitimacy. The “non-brothers” as Réjane Sénac describes women, but also other “guest” populations – or spare parts – in the “human family”, have to define their identity and role as being “different” to those who were previously acknowledged as “similar”.

Should we then replace fraternity by an unambiguous notion to describe the kind of human beings who immediately and unconditionally deserve to be treated with dignity and equality, as well as solidarity? The concept of “adelphity” might well be an acceptably non-gender-specific way of expressing the term “fraternity”, and thus making a small step forward towards equality.

Tou.te.s adelphes, tou.te.s singulier.es, défini.es par soi-même et non par rapport à une norme.

Of course, lexical substitution alone cannot establish equality in rights, dignity and facts. But Durkheim’s beloved “collective consciousness” centers around values and symbols, so this inclusive neutral of “adelph” could be a basis from which to re-construct the strength of the matrix bond, free from a binary opposing “brother” and “non-brother”, “same” and “different”, women and men, national and foreign, old and young, etc.

In fact, all adelphs share a common destiny and each individual is defined within him or herself, and by him or herself and not by assimilation, comparison or opposition to a gender, an origin, a skin color, a generation, etc.

Article by Marie Donzel for the EVE Program

Translated into English by Ruth Simpson

[1] (Arise) Children of the matrix! – The lyrics to the first line of the French national anthem are “Allons enfants de la Patrie”, usually translated as “Arise children of the Fatherland”.